I’ve been doing a lot of reading lately on the history of libraries, the level of literacy in the ancient and medieval world, and the manufacture of papyrus, parchment, scrolls, and codices. It’s a fascinating study, and sometimes painful, especially when the histories recount the destruction of libraries through deliberate acts or simply neglect and decay.

Sometime around 1320, the church of St. Mary the Virgin in Oxford set aside a room to hold books for the University of Oxford as an institution. The individual colleges had libraries, but their holdings were often available only to members of college. The new library would hold books — manuscripts, of course, at that date — which could be used by all members of the University and its colleges. When the youngest son of Henry IV, Humphrey Plantagenet, Duke of Gloucester, brother to Henry V and Lord Protector of Henry VI, died and left his then-considerable collection of 281 manuscripts to Oxford University, the University built a luxurious reading room over the new Divinity School to house the entire library.

Unfortunately, the library did not survive the Reformation. Like so many other libraries in England, institutional and private, the University library was purged to remove all traces of Catholicism. Most of its books were burned, and Duke Humphrey’s Library room became a meeting and lecture room for the Faculty of Medicine.

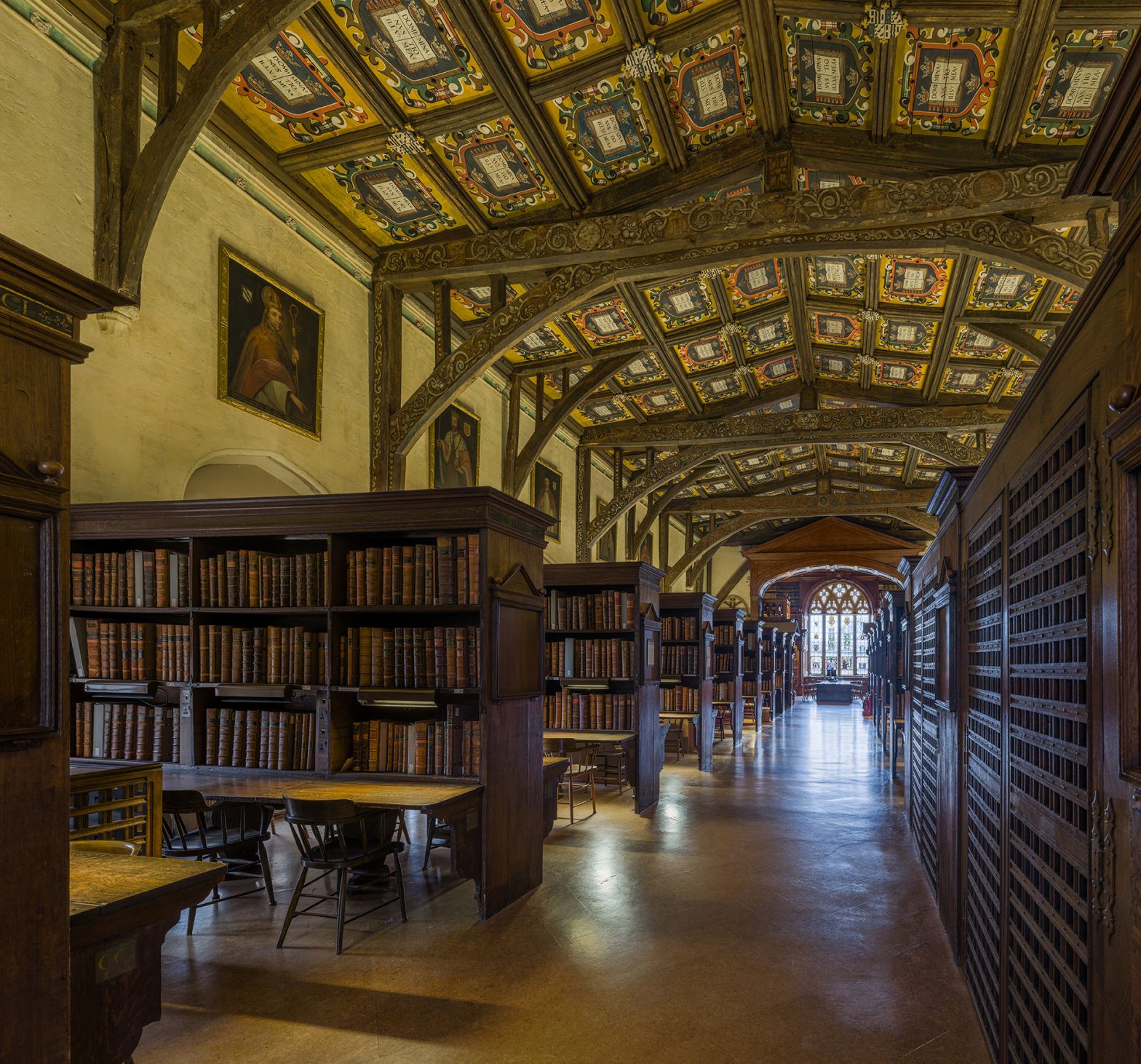

But the vision of a library “for all students” did not entirely vanish. A Fellow of Merton College, Thomas Bodley, retired from active teaching and decide to “set up my staff at the library door in Oxon; being thoroughly persuaded, that in my solitude, and surcease from the Commonwealth affairs, I could not busy myself to better purpose, than by reducing that place (which then in every part lay ruined and waste) to the public use of students”. He oversaw the refurbishing of Duke Humphrey’s Library, from reinstalling shelving and repainting the walls and ceiling to obtaining books for the collection, some of which he donated himself. When the library opened to members of the University and its patrons on November 8, 1602, it housed 2500 books.

The invention of the printing press made books more widely available, and more easily tracked through their publishers. Bodley secured an agreement that one copy of every book published in England and registered would be deposited in his new library. While he died in 1613, the University carried out the terms of his will to create not only a book repository but also a museum and gallery for preserving artifacts and paintings. Subsequent generations expanded the rooms and the collections: the Bodleian Libraries of Oxford now hold some 13 million items, including manuscripts, maps, music sheets, photographs, and “ephemera” — those materials printed for a specific purpose, like menus and playbills.

Some years ago, I sat in the Duke Humphrey reading room, admitted because I was able to produce a letter of introduction from the Chair of the Department of History at UCLA, himself an Oxford MA, and only after swearing that I would not remove any books from the library, nor mark or deface anything owned by the library, nor to kindle any fire or flame in its rooms. The library aid took me to a table, and laid before me four priceless fourteenth century medieval manuscripts on astronomy for my review. It was a heady moment.

The Bodleian Libraries have embraced modern technology in their mission to make their collections available to the widest possible audience. You no longer need to travel to Oxford to view some of the gems of their collection: you can do it online, from your home, through the Digital Bodleian portal.

It isn’t quite the same as sitting in in a bay in Duke Humphrey’s, with the ceiling coat of arms inviting divine inspiration Dominus illuminatio mea, towered over by polished wood shelves filled with leather-bound books with gilt titles, immersed in the wisdom of the past and the promise of new ideas…but it will do for today.