When I was in grammar school, I read a lot of biographies of men and women from different countries and time periods. While women frequently faced specific prejudices because they were women, men faced similar prejudices because they were poor, or from the wrong family, or not educated at the right university. It seemed that every individual faces problems unique to a time, place, and a personal character. My conclusion: we need to be prepared to rise to the occasion, whatever it is.

By the time I graduated from college, the feminist movement was in full swing, and one of the myths that gained popularity was that women had been suppressed and, in particular, deprived of educational opportunities. I knew, from those books I’d read as a kid, a number of women both educated and influential, so I started collecting examples of two sorts by way of rebuttal: sort 1) the idea that women were expected to be properly educated to carry out their responsibilities, and sort 2) specific women with fantastic educations or academic accomplishments (yes, they made me envious!). For the first sort, I could find artistic images as a start: artisans in the ancient world created vases with paintings of women reading and those in medieval Europe adorned churches with carvings of women saints holding books and the Virgin Mary reading to the infant Jesus.

And for the second, there were the women themselves who were educated and often were even teachers, and who show up in the least likely times and places.

At the turn of the millennium (ce 1000), access to education for both men and women was limited to those with leisure time to study and the money to hire instructors, or those fortunate enough to display talent or a religious vocation. Guglielmo di Puglia writes of the city of Salerno at the beginning of the second millennium, that it not only produced fruits and crops fine wine and fine ornaments, but also men and women who exceeded in the art of medicine after training at the Schola Medica Salernitana – a school run by women. Throughout Europe, Benedictine nuns were expected to read, as were Benedictine monks, although their reading matter would have focused on Biblical texts, the Rule of St. Benedict, and other spiritual works.

But there were women who were educated in a classical tradition — those of nobility and wealth — who were, because of their education, able to take advantage of their position to influence their contemporaries and posterity. At the court of the Byzantine emperor Alexios I Komnenos, when the princess Anna Komnene was born December 1, 1083, she was designated the imperial heir, and so received an education designed to prepare her to govern. She studied the classical Greek language (different from the Byzantine version of koine Greek she spoke), literature that included Homer and the Greek historians, rhetoric, astronomy, medicine, history, geography, and mathematics. Recognizing her skills with both medicine and logistics, the emperor put her in charge of the hospital he had built in Constantinople, where she worked as administrator, medical instructor, and doctor. She married Nikephoros Bryennios, the Emperor’s general and the direct descendant of previous emperors with a strong claim to the throne. When Alexios died, Anna was implicated in a plot to claim the throne as firstborn and wife of an heir, but her younger brother John succeeded in his own claim, and Anna was banished to a convent for the remaining thirty-five years of her life.

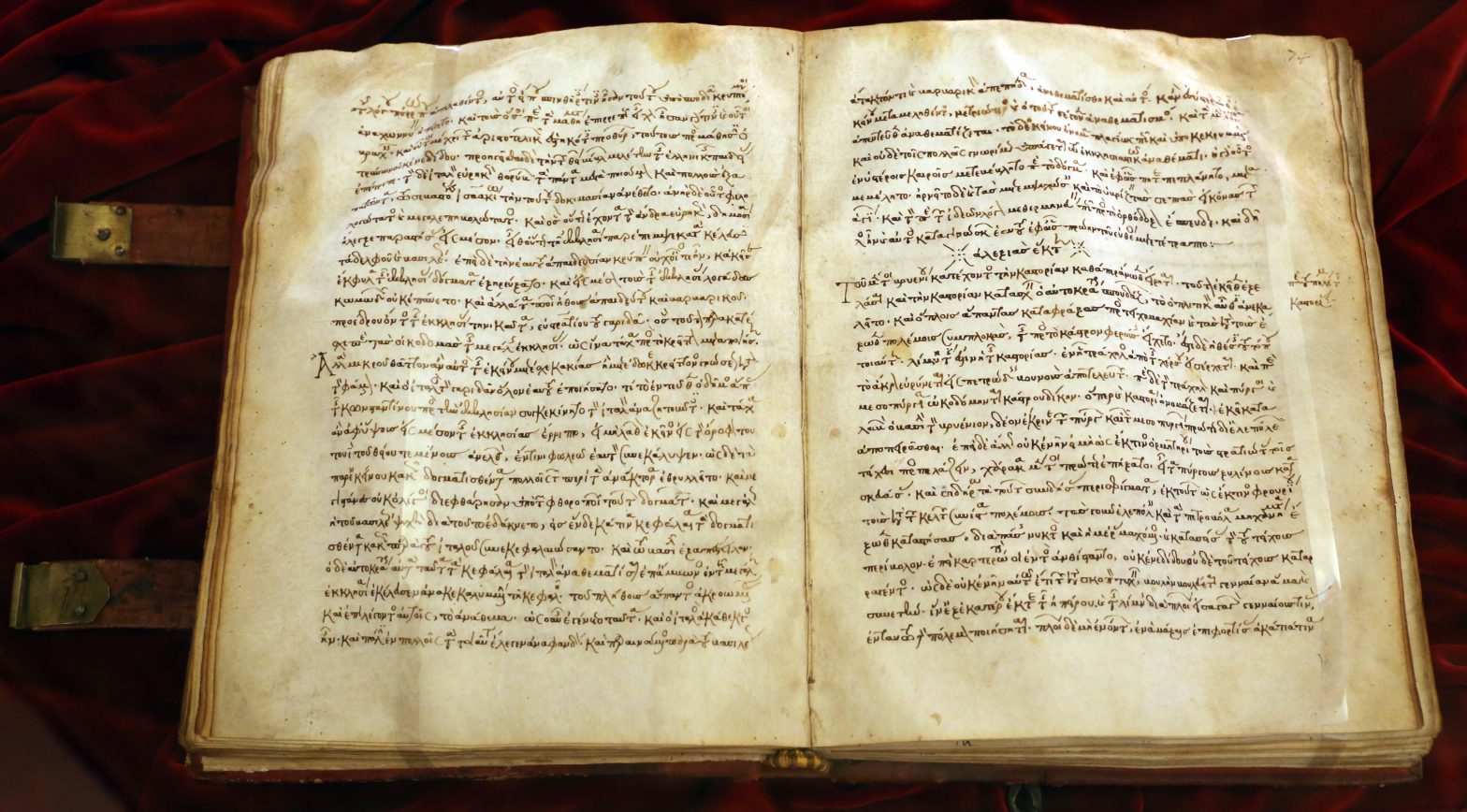

She could have lamented her fate and sulked, but instead, she studied philosophy and gathered around her scholars interested in Aristotle’s ideas and in the history of the Byzantine empire and in the fundamental question that still plagued her: how to reconcile the literature she loved with her faith. She decided to complete the historical work her husband had started, and produced the Alexiad, an account of her father’s political relations and wars, which included the First Crusade. She drew on first-hand accounts of her father’s courtiers and her relatives, as well as imperial records. Although her work is hardly impartial, since she tended to praise her father and portray his enemies unfavorably, it is considered reasonably accurate. In her effort to create a model history, Anna wrote in Attic Greek, using the literary styles she had learned from reading Thucydides, Polybius, and Xenophon.

When she died, George Tornikes, the Metropolitan of Ephesus, delivered a long funeral oration recounting Anna’s accomplishments. He describes in particular something the Alexiad doesn’t cover: Anna’s creation of a community of scholars who re-examined classical philosophy in an attempt to identify its true and useful teachings and synthesize them with Christian dogma. According to Tornikes’ account, Anna organized lectures, paid for tutors to conduct open classes, and encouraged the production of commentaries on Aristotle’s works.

In Byzantium, the study of Greek philosophy and of Aristotle in particular had lapsed after the reign of Justinian and the closing of Plato’s Academy in A. D. 529, but it found a new life in the eleventh century, spurred by men who were brought together in Anna’s philosophical school. The renaissance of classical philosophy in Constantinople spread westward to the new universities in Italy and France, and eastward to the courts of the Abassid Caliphs, carried in the commentaries of the newly-copied manuscripts Anna commissioned.

Faced with exile from court, mourning the death of father and husband, Anna could have given up her search for truth and a reconciliation of the life of the mind and a life in Christ. I have to ask how different my own world would have been if she had retired to a quiet monastic life, and not inspired those around her to provide the basis of a revolution in thought that would lead to the rise of universities in Europe.