On this day in A. D. 735, Prince Toneri, son of Emperor Tenmu, died without ever ruling, but since his son Junnin did come to the throne, Toneri was posthumously granted an imperial title, Emperor Sudoujinkei. Although he did exercise some political influence as a member of the imperial family, Toneri’s great contribution to Japanese culture was as the chief editor of the Nihon shoki, the Chronicles of Japan. which was finished and presented to the emperor in A. D. 720.

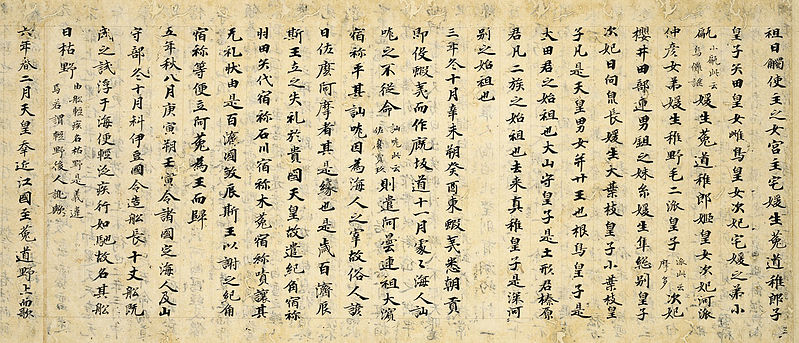

Together with the Kojiki collation completed in A. D. 712, Nihon shoki preserves the mythological traditions of the origins of Japan and the histories and genealogies of its great families, but the two works, produced in the same family, are strikingly different. As a formal history intended to impress foreign dignitaries, Nihon shoki consolidated well-documented creation myths in order to establish the authority of the imperial family. It drew on official state documents which it cites at length, including Chinese sources, and it evaluated past emperors for their virtues or bad judgements. It was written in classical Chinese, the language of the Spring and Autumn annals of China’s Eastern Zhou dynasty almost fifteen hundred years earlier, which was still taught in China, Korea, and Japan.

In contrast, the Kojiki uses less formal means to establish the imperial Yamamoto family’s right to rule by consolidating different family versions of the myths and legends of Japan’s origins to create a consistent version. It drew not on official source documents, but on stories told at court and by the important clans. It, too, was written in Chinese, but used a phonetic syllabary to express Japanese names. Where the Nihon shoki creates chronologies by setting the dates of imperial rule (with some inaccuracies), the Kojiki instead contains the hitherto oral history of the clans, anecdotal stories memorized by household scholars and servants.

These official histories became core elements of the classical literature of Japan, as the works of Herodotus and Homer did in Greece, and those of Livy and Vergil did in Rome. They can challenge our sometimes narrow defining of what is classical, and entice us to discover how others determined what was useful and valuable to learn. In their portrayal of familiar stories in a different setting — of divine encounters, fraternal rivalries, loyal friends, and noble enemies — they can even tell us something about ourselves.