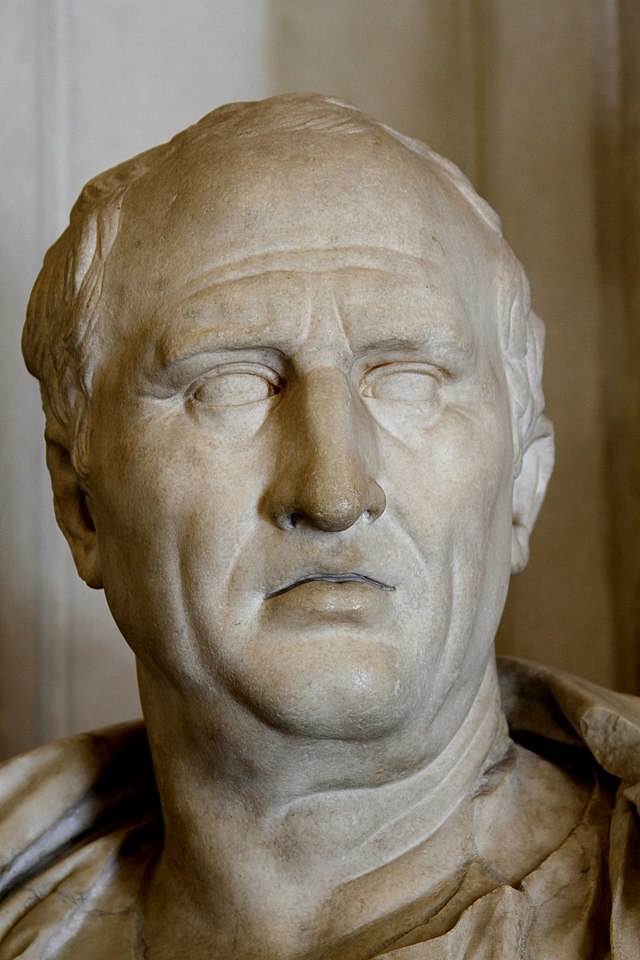

On December 7, 43 B. C., Marcus Tullius Ciero died at Formia, Italy. He lived in the chaotic period that included the end of the Roman Republic and the beginning of the Roman Empire, and it is impossible to assess how thoroughly the observations and descriptions in his speeches, dialogues, treatises, and letters shaped western civilization. Here we have space to reflect on only a bit of history and a few of his works, but I hope it whets your appetite to learn more.

Cicero was born into a wealthy family in the equestrian order, a class of Roman citizen with significant property rights, and he was able to study the Greek language, philosophy, logic, history, and rhetoric from Greek teachers who had fled wartime conditions in Greece. After serving in the millary as a teenager, Cicero resumed his education and traveled to Athens and Asia Minor to study with the most famous teachers there. Then he returned to Rome to take up political and legal careers, ascending the cursus honorum, the offices of Roman political service as well as serving as defender and prosecutor in the courts. In 63 B. C., Cicero discovered and thwarted Catiline’s attempt to overthrow the Republic with a series of speeches written for delivery to the Senate, which have since held a place of honor in the Latin curriculum.

It was the height of Cicero’s official political career: he never again held the consul’s office. It is far beyond the scope of this brief entry to describe Cicero’s subsequent activities. I will only take the opportunity to point out how a few of his works shaped medieval European philosophy, Christian theology, and literature, as well as classical education.

Cicero’s Hortensius discusses the reasons for pursuing philosophy. Unfortunately, we no longer have the entire work: only fragments quoted in other works exist. Still, complete manuscripts survived long enough to influence Martianus Capella, whose De nuptiis Philogogiae et Mercurii describes at length the seven handmaids of Philologia (Learning): Grammar, Dialectic, Rhetoric, Geometry, Arithmetic, Astronomy, and Harmony (music) that formed the basis of classical education in early medieval Europe.

Another who read this work was St. Augustine of Hippo, who tells us that it encouraged him to study philosophy, which eventually led to his conversion to Christianity.

Still others were influenced by Cicero’s letters. Among these was Petrarch, who came across a hitherto unknown collection of letters in the Chapter Library of Verona Cathedral, which led him to champion the study of ancient Latin and Greek sources, one of the fundamental motivations behind the Renaissance.

It is hard to imagine what our modern world would look like without Augustine’s theology or the Renaissance, or what classical education would look like without its emphasis on clear expression represented by the trivium.

Finally, consider this: If we put together all of the Latin works written during his lifetime (106 – 43 B. C.) that we still have, more than 75% were written by Cicero. He knew Greek and read Hellenistic works extensively, and created Latin terms when he needed to express a Greek philosophical idea for which there was not yet a Latin word, such as humanitas and qualitas. The Latin language we study now would not exist without Cicero.